Banataba | Faustin Linyekula & Moya Michael

Met Museum, Velez Blanco Patio

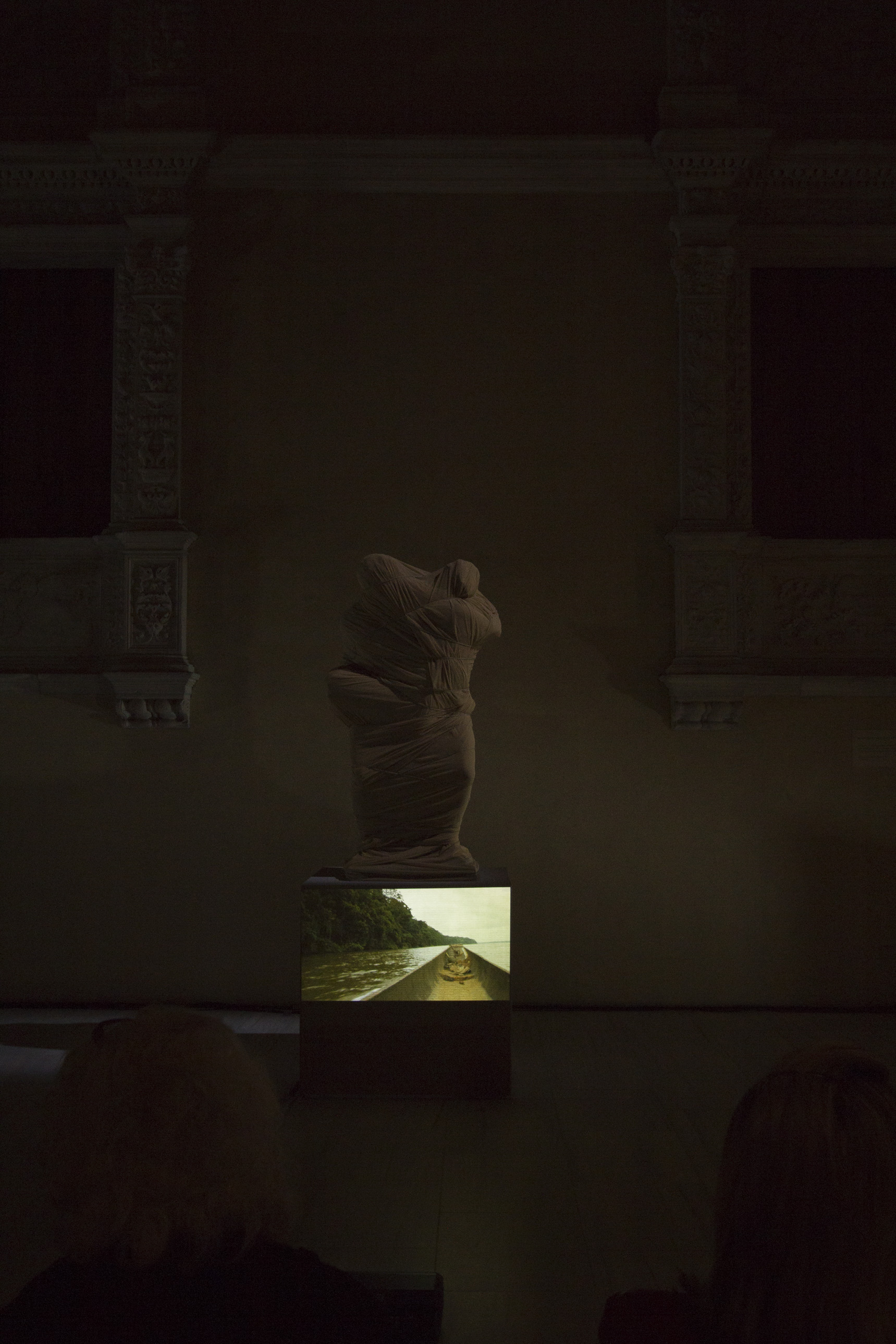

A small group has gathered to watch Mr. Linyekula’s performance Banataba on a Sunday afternoon at the Met. The are two perceived stages: an elevated stage to the left of the audience and the remaining space in the hall serves as a second stage. To the audience’s right, there’s a sculpture that has been wrapped in cloth and is held in place by a rope. A video is projected onto its base in which we watch a canoe gliding along a river (presumably the Congo river) as we wait for the performers to enter the room. The chatter within the room runs parallel to the host of voices emanating from the video. The distant voices alternate between everyday discourse, laughter and singing and eventually the video transposes us to a place where we witness a group of villagers talking, singing and chanting. There’s a playful & almost taunting tone in their voices.

Mr. Linyekula & Ms. Michael enter the space from opposing points as the lights are dimmed. They are both draped in black cloth that has been bound to their bodies: their movements are contained and restricted. Their cloths remind me of the Ghanaian funeral attire worn by men, which is typically draped around the body in a similar pattern. Mr. Linyekula joins the singing, transporting the tune from within the video into the room. The voices co-mingle for a short while and Mr. Linyekula’s singularly emerges, carrying on a singsong tune. On his arms, he carries something that is wrapped and bound, which he passes along to Ms. Michael as they meet in the center of the space. They continue to pass the wrapped item back and forth, between themselves.

It’s hard not to imagine that the audience is either witnessing or partaking in a ritual. The lecture-style seating arrangement does not afford a good view to those of us sitting in the second or third rows, making the performance feel more distant than probably intended. After the procession, there is an unroping and unrobing of their garments and the two performers settle onto the elevated stage. Mr. Linyekula then breaks into a narrative and recounts the journey that has brought all of us into the same space. How is it that we are all gathered in this room?

We learn that a Congolese object in the Met’s storage - an object that has yet to meet the public’s eye because its origins are “questionable” - was precisely what moved Mr. Linyekula to create this performance. The object emanated an energy that pushed him to delve deeper into his own history. He asks, ‘what if we value objects based on how they make us feel rather than just their visual / aesthetic attributes?’ He questions how it possible that of all the objects displayed at the museum, the one that evoked an unshakeable feeling within him is the one that curators have deemed unworthy of showing.

Mr. Linyekula proceeds to tell us a personal story, one of self-discovery in America, far away from where his parents originated, and even further removed from his ancestors and their ancestors. The beauty of his encounter with the aforementioned object is that although the artifact removed from its place of origin, it retains its essence and power to move him regardless of this Entstellung across continents. It’s a testament of how artifacts contain within them an energy to connects us to our ancestors.

Mr. Linyekula continues to unwrap the bundle in front of him, together with Ms. Michael, and there’s a deafening silence that is interrupted by an electronic noise similar to that of a theremin. It is reminiscent of the sound you usually hear, when a sound and space barrier is broken in a film. We emerge on the other side of the barrier, unmistakably in the Kongo. Together, the two performers attempt to arrange the individual pieces they uncover as if they are assembling the pieces of a puzzle. They glean hints from different actions, such as listening to the sounds of hollowness and density produced by hitting the individual pieces against each other. In doing so, they search for pieces that belong to each other through a harmonious noisemaking. As they progress, it becomes clear to them and us that the unwrapped figure is in fact a wooden artifact in the image of a human body. They pause to call upon guidance from their ancestors as they assemble the pieces in front of them.

The summoning of ancestral spirits takes on the form of a ritualistic dance that transforms Mr. Linyekula into a medium for communication and rebirth. Ms. Michael aides in the process, and at times stretches Mr Linyekula’s limbs as if it were that of a newborn baby's being massaged and lengthened, and in some ways toughened for the world. It reminded me of Ghanaian mothers I have witnessed doing the same to their newborns. Mr. Linyekula retreats into himself with a pensive, distant gaze on his face in his eyes signaling that he’s entered a different state of consciousness. His narrative voice, which has guided us through the performance thus far, emerges from a trance-like state as a language that is unintelligible to me.

Mr. Linyekula does not specify where in the Kingdom of Kongo he is from; rather, he traces his origin through the ancestors know to him. There is a modern desire to label that he does not afford the audience. By refuting labels and fictitious borders imposed on his people, he edifies his ancestral lineage by recounting history in a way that is in fact meaningful to him. He counters the accepted narrative of what the Kongo has become as a result of events such as the Berlin Conference, which took place in 1884-1885, during which King Leopold (of Belgium) was given what is now known as the DRC as private property. The conference established what we now know and have accepted as the borders of African countries. It divided kingdoms, erased cultures and ushered in the brutal pillaging of a continent by the 14 Europeans countries that partook in the conference.

Mr. Linyekula breaks into a monologue, signaling that his consciousness is with us again, during which he traces his ancestry from his time in New York back to the Kingdom of Kongo. He expresses a deep desire to explore his ancestry beyond what he knows from his parents. He is interested in going back to a time that is historically untraceable in writing, when narratives and lineage lived through oral tradition, passed on through generations for whom these narratives were most precious. These are narratives that held value prior to a written history, devoid of subjugation from the filters of outsiders.

Together with Ms. Michael, Mr. Linyekula begins to reassemble the scattered pieces anew. This time, it happens in a more informed manner - as if the ritual has imparted him with some divine knowledge. The spiritual journey, or ritual, we witness Mr. Linyekula undertake brings him closer to ancestral and familial knowledge that would otherwise be difficult to attain.

The symbolic time and space barrier is transcended again and Mr. Linyekula’s narrative brings us back into the present. He returns to the artifact in front of us, which we learn is a replica of the one he first saw in the Met’s archive. It was made specifically for this performance and originates from the Kongo. As its keeper, he had to undergo a secret ritual to endow him with the knowledge to care for it, before it came to New York.

Once my mind wandered back to the room at the end of the performance, I knew I had been transformed in a way I could not yet articulate. As I looked around the room, I wondered whether my experience was shared by the majority Western audience. How our understanding of Mr. Linyekula, and what he had experienced in making this performance would differ from individual to individual. In its aftermath my thoughts lingered on the proceedings of the secret ritual Mr. Linyekula underwent in the Kingdom of Kongo - something he said could not be shared with this audience as mandated by those who led it. He withheld from us, rightfully so, something that maintains a sacredness at the core of his heritage. It is something that cannot be made visible, coveted or taken away.

Written by Nana Asase (09.10.17)